By Bridget Lawless

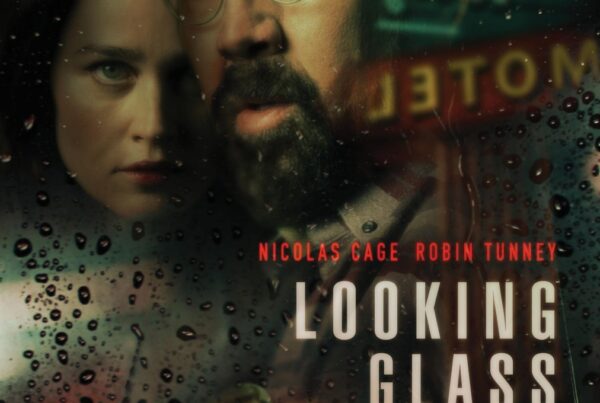

Over the last decade or so, the number of films and TV dramas in which women are abducted, violently assaulted, stalked, raped or murdered has got a bit silly. It’s become quite the thing to show women in terror, in as many ways and situations as possible. The build-up and climax of a woman’s fear is constructed for the viewer not only in the way it’s acted, but how it’s shot, what is focused upon, and the way in which music or sound engineering raises the tension.

Let’s take a look at how a story that features sexual or physical violence to women gets to screen. Basically, it’s the result of large number of people making positive decisions to bring it to the world, often in the hope of getting it widely seen, winning awards, and making as much money as possible. Did all those people consciously decide to show or imply graphic violence meted out to a woman – think that was the best they could come up with? Probably not, or not entirely. And yet… That’s what’s delivered, over and over again. So how do they get there?

Someone has an idea. Be it good, bad, praiseworthy or offensive, that remains to be seen, because what survives the process may well not be how it set out. Or, it may well be. A good idea can be challenged and eroded, warped and hijacked along the way and turn out a distasteful mess. Equally, a bad or distasteful idea can swim smoothly into production, unchallenged by those who could have made better creative decisions, and even win awards. You see, while casting, acting, production values, costumes, all have recognised standards, there is no real standard for something as simple as whether it’s a good idea to keep depicting women being brutalised.

The idea for a film or TV drama may or may not start with the writer – sometimes directors or producers come up with ideas and attach a writer to the project. But for this exercise, we’ll assume it’s the writer’s own.

From their seed idea, the writer creates an outline for a thriller, ie, thinks up characters and the plot, from which a script or series of scripts follow. The writer’s agent might get involved if they’re pitching a spec script, so they also have to get behind the project and sell it. Perhaps they make some suggestions, too.

With a bit of luck (a lot…) a development executive likes the look of it, and persuades their producer to take it on. The script could then go through a long development period ( or ‘hell’, as it’s known) with input from the development executive, script editors and the producer to whom they all answer. Everyone may be thinking, how can we make this as edgy, different, daring, as possible? How far can we push this to get it noticed? They’ll also be aware of the other fare already on screen or in development that their project will be up against. They’ll be bearing in mind what the various executives up the line want to see; their personal preferences, their definite no-noes, their likes and dislikes, their weaknesses. If those execs happen to be deeply misogynistic, they’ll find themselves playing to that, too.

So far, along this short journey, the writer may have had to cross lines they aren’t too happy with. But they want the gig – and they want to keep it… (every writer’s contract has a clause that says you can be kicked off even your own project and replaced.) There’ll be dialogue, of course, but at some point, for the writer, pushing back risks losing the job. The Script Editor may have nudged the writer just that bit further – grinding down their objections, maybe poo-poohing them, telling them it’s needed/OK/exciting/daring/will make them stand out. Basically pushing at their boundaries until they coerce the writer into going along with whatever they had misgivings about. However reluctantly, and often against their better judgement, the writer has given their consent.

If the project is a film, the director will be brought on board at this point. They’re part of the package to bring to the money people. If it’s a TV show, the director is more likely to be sought once the project gets the go ahead, unless it’s a writer/director at the helm.

A director has a huge amount of power in the production mix. It is essentially their vision being realised, although producers can and do sometimes override decisions before and during filming and throughout the editing period. So when directors’ names are being tossed around by the producers, (particulalry with feature films) they’re thinking about who will attract investment, appeal to star names, bring something exceptional to the screen. Slightly less important is who they are as a person. A big ego is expected – it’s a big ego job – but sensitivity to fellow human beings is less important. Respect for women? Yes, it’s of some concern these post #Me Too days – no one wants that kind of publicity now. But will that a director will respect an actress when he (or she) wants to push against her boundaries? That’s a much greyer area. Ultimately, a director’s ability to attract money and names is much more important than his (or her) respect for women.

Everyone, from the start of this process, whether in film or TV, has been working towards the one magic moment, the Holy Grail at the end of development – the Green Light. This is the point where a film or series gets the go-ahead from the money people. This is the outcome of all that hard work, collaboration, creativity, excitement, and of all the bullying, threatening, backing down, firing and complicity. Already, it is been a long and complex collusion.

Again, more dialogue. More arguments, until a final decision is reached. At any point along the line, the pre-existing decisions of the writer, script editor, development execs and producer, could have been ditched in favour of something new, or someone else, for better or worse. The strongly held beliefs or passions of the writer may no longer be represented in the script, or mentioned in meetings. The original writer may have parted company with the project, or been kicked off it. The direction the script has taken might make it barely recognisable from the original versions – and what’s on the page now may no longer in any way reflect the integrity of the project in its infancy.

So if you’re wondering how films and television dramas come to our screens, night after night, filled with women being subjected to pain, terror, physical and sexual assault, why they’re abducted, raped and murdered, or just found dead at the outset, as a prop for some detective’s journey, and all for our viewing pleasure, you can be sure it’s not any one person’s achievement, or fault.